South Dakota's Rich German Heritage Enhances Language Study at USD

“Expectations in most German classrooms are that students will travel to Europe in order to study, use or interact with the German language and culture,” he said. “German could still be studied effectively in the United States using local resources without this expectation of travel. German can be practiced right here in the Midwest as well.”

Over 33% of South Dakota residents identify as German- American according to 2022 data from the U.S. Census Bureau, and just an hour’s drive away from USD’s campus in Vermillion sits a small town representing a unique part of that heritage. Freeman (current population 1,312) was originally home to Native Americans from the Oceti Sakowin Nation when the 1862 Homestead Act brought settlers from far and wide to the South Dakotan prairies. In Freeman’s case, a group of ethnic Germans who had lived in Russia for a century decided the spot 35 miles due north of the territory of Yankton was an ideal place to relocate in the face of an impending revolution and efforts to Russify the country’s population.

The southeastern South Dakota city became home to a number of different groups of German speakers, including Lutherans, Reformed Christians and three different Anabaptist groups – Swiss Amish, Hutterites and Low German Mennonites – all of whom retained their language and adherence to religious and cultural traditions in their new country. Freeman’s independent, nonprofit Heritage Hall Museum & Archives contains an extensive collection of artifacts related to the area’s Native American and German immigrant history.

These characteristics also make Freeman a valuable resource for exploring the German language and aspects of German heritage in the U.S., said Bates, who was awarded a South Dakota Humanities Council grant in 2021 to perform research in the Heritage Hall Museum & Archives, where he now serves as vice president of the board of directors.

All levels of his German classes include lessons on culture, but Bates delves most deeply into South Dakota heritage in an upper-level seminar on German in South Dakota. In this course, students explore the state’s history of German immigration, schooling and education, and literature and music. “And of course we end with food,” Bates said. He noted that kuchen, the German pastry, is South Dakota’s official state dessert.

The class’s sweet ending follows extensive work with artifacts – including poems, stories, letters, personal histories and books all read and discussed “auf Deutsch” (in German).

One nearly 200-year-old math primer presents myriad learning opportunities on the aesthetics of publishing, importance and meaning of family heirlooms, and interpretation of German-specific typefaces and handwritten scripts used by the German diaspora until the early 20th century, Bates said.

The math primer belonged to Daniel Unruh, who was born in Ukraine in 1820 and was one of the first German settlers in Freeman.

His math book, brought to the U.S. as a cherished heirloom, includes colorful drawings among the carefully written calculations. “This connects back to the illuminated texts of the medieval ages,” Bates said.

The book’s font reveals another history lesson. “Mennonite students were expected to learn model penmanship by copying pre-exisiting books that served as templates. ‘Rechenbücher,’ or arithmetic books, were very common,” Bates explained.

Only boys copied math books, linking this practice to their future in the business world.

Another artifact Bates found in his research gives students in his classes the opportunity to practice reading and understanding an argument in German.

“Die Deutsche Sprache und Ihre Bedeutung” (“German Language and Its Meaning”) is a 41-page pamphlet penned by J. John Friesen, a former English professor at Freeman College, a small Mennonite college existing from 1903-1986. It now serves as a K-12 private school called Freeman Academy.

“We read the pamphlet together as a class and discuss his arguments,” Bates said. “I thought there were some interesting things in there, but the students have been critical and have taken apart his arguments and suggested better ones for why you should learn German. I was impressed.”

Students have completed projects and papers throughout the course, including some students who have researched family connections to the area.

One such student is Aundria Lankford, who liked her time in Freeman’s Heritage Hall Archives so much, she became a summer intern there after she took Bates’ class.

Lankford is a recent graduate who majored in German and international studies and minored in Russian. The opportunity to study both German and Russian is what brought her to USD.

“I grew up as a military kid, so I was born in Germany,” Lankford said. “It’s my heritage. My mother’s family is German, but I didn’t grow up speaking the language.”

Lankford lived in Germany after graduating from high school in the U.S. She then returned stateside to pursue higher education. Bates’ class on German in South Dakota tapped into many of her interests.

“I’ve always enjoyed those classes that combine language with storytelling,” she said. “I was curious about how we got these little pockets of intense German culture in the Midwest.”

Her knowledge of both German and Russian helped Lankford complete a project on linguistics and dialects in the region. Reading primary sources in the Heritage Hall Archives made her appreciate preparatory classwork Bates had provided on the Gothic Fraktur font and Kurrent handwritten script found in the German publications in the archives. “Dr. Bates gave us a great toolbox,” she said.

Learning about the Germans in Freeman and throughout the state brought her language learning to another level, Lankford said.

“In classes like this that are taught in German, you still learn grammar, but you learn by doing,” she said. “You learn by participating rather than memorizing vocab lists. Sometimes it hurts. Sometimes it’s frustrating. But you’re learning twofold.”

Lankford had a chance to delve deeper into research in the Heritage Hall Museum & Archives during a summer internship in 2023.

The Heritage Hall Museum & Archives features thousands of items on display, from Native American artifacts to musical instruments and agricultural machinery. Also on the grounds are restored historic buildings moved to the site to illustrate early settler life. One of these buildings is the Deckert House, a frame house built in the 1880s by settler Ludwig Deckert. Many of the house’s features are indicative of German-Russian architecture, including a massive chimney in the center of the house.

Lankford’s main task during her summer internship was building an interactive computer kiosk that illustrated the history and features of the Deckert House. The kiosk now sits in the museum’s main hall and is regularly used by visitors.

This museum work has expanded Lankford’s ideas for future careers.

“My view of what I could do with my life used to be really narrow,” she said. “Since I was studying foreign language and politics, I thought I had to work for the government or the U.N. After working at the museum and guiding guests through the exhibits and telling stories, I could see people’s faces light up with the understanding of just how interesting this little part of South Dakota is. Now I feel like I could work in a lot of different places as long as I have a positive impact on people.”

Upper-level German students are not the only ones who get to learn about and experience the state’s German heritage. Students in introductory language classes have attended Schmeckfest, Freeman’s annual festival celebrating this culture.

The 2024 Schmeckfest fell on USD’s spring break, so a small group of Introductory German I students accompanied Bates to Freeman on a brisk but sunny March morning.

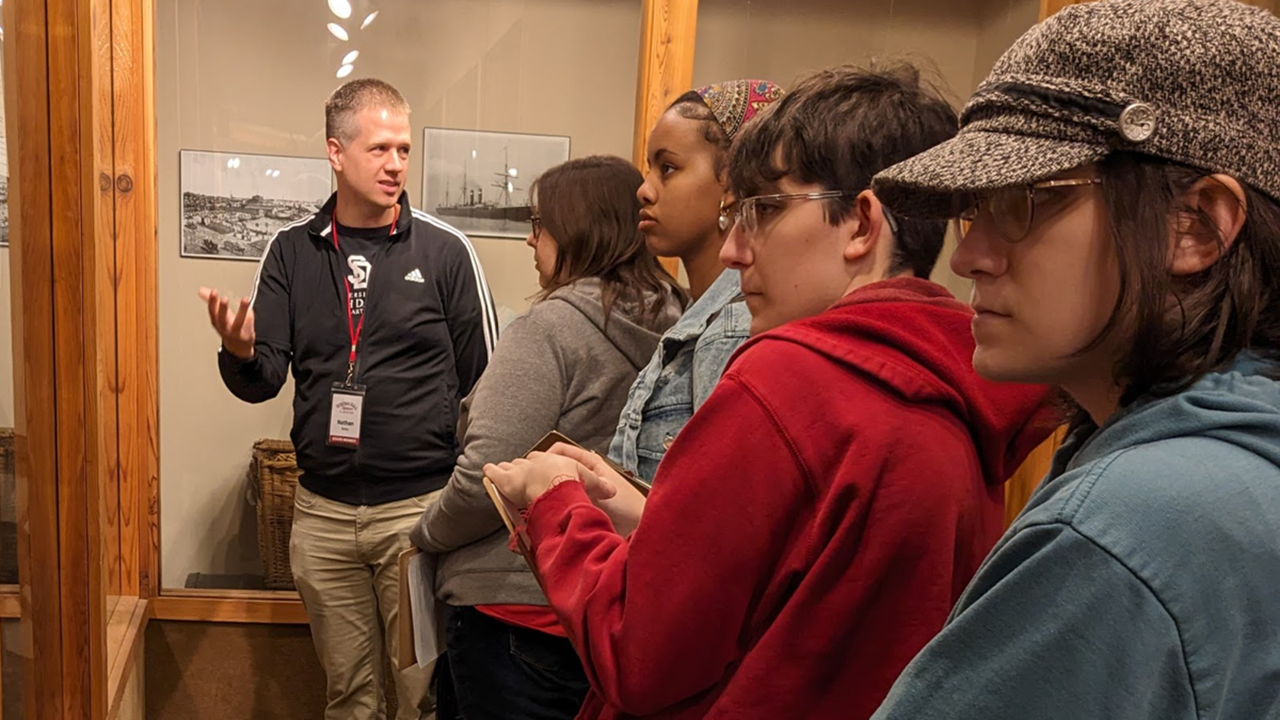

Bates began the daylong field trip with a discussion of the history of the German immigrants. He then brought students through the Heritage Hall Museum exhibits and the restored historic buildings on the grounds. Describing some of the extensive collections in the museum and archives, he emphasized the immigrants’ religious customs. “There are so many Bibles,” Bates told the students.

Students listened as Bates read a framed poem on the wall of the Deckert House. They also stood in the chilly confines of the Johannesthal Reformed Church and imagined unheated services in this building in the early 20th century.

Efrata Walelign, a political science major from Ethiopia, said German is her favorite class at USD. She found the trip to Schmeckfest helped deepen her understanding of the language and how the German diaspora maintained its culture in new locations.

“I got the chance to learn more about the immigration of Europeans to this part of the United States and how they managed to navigate their lives,” she said. “It was really interesting to see and learn about the museum and how some initiatives were taken by these settlers and how it grew. The community feeling with the people and how it was represented by eating together and the connection between them was also interesting.”

Michaella Hesman, a history major from Woodbine, Iowa, said the trip to Schmeckfest demonstrated the interactive approach Bates takes to teaching German.

“Dr. Bates makes learning German fun by finding different activities, songs and short films that go with each lesson,” she said. “I’m glad that I went to Schmeckfest because I experienced things there that can’t be taught in a classroom, like seeing how passionate people were about the crafts, demonstrations, the festival itself and the story of the Germans who came to Freeman.”

For his part, Bates hopes to expand on this work connecting local history and culture with language learning by creating an open-access textbook for high school and college students.

“Learning about the language of our ancestors honors them,” he said. “Fostering our German heritage brings history alive and opens doors.”